Abstract

This paper is dedicated to the measurement of (or lack of) electoral justice in the 2010 Electoral College using a methodology based on the expected influence of the vote of each citizen for three probability models. Our first contribution is to revisit and reproduce the results obtained by Owen (1975) for the 1960 and 1970 Electoral College. His work displays an intriguing coincidence between the conclusions drawn, respectively, from the Banzhaf and Shapley-Shubik’s probability models. Both probability models conclude to a violation of electoral justice at the expense of small states. Our second contribution is to demonstrate that this conclusion is completely flipped upside down when we use May’s probability model: This model leads instead to a violation of electoral justice at the expense of large states. Besides unifying disparate approaches through a common measurement methodology, one main lesson of the paper is that the conclusions are sensitive to the probability models which are used and in particular to the type and magnitude of correlation between voters that they carry.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

It requires that the “votes” of any two persons should have the same influence.

- 2.

One man, one vote (or one person, one vote) is a slogan used by advocates of political equality through various electoral reforms such as universal suffrage, proportional representation, or the elimination of plural voting, malapportionment, or gerrymandering.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

This indirect election system (In German: Dreiklassenwahlrecht) has also been used for shorter intervals in other German states. Voters were grouped into three classes such that those who paid most tax formed the first class, those who paid least formed the third, and the aggregate tax revenue of each class was equal. Voters in each class separately elected one-third of the electors (Wahlmänner) who in turn voted for the representatives in Prussia from 1849 to 1909 and the law of sieges(called the law of double vote) created among the voters (only old enough males paying a critical amount of taxes were voters). For more on this electoral law, see Droz (1963) and Schilfert (1963).

- 6.

University constituencies originated in Scotland, where the representatives of the ancient universities of Scotland sat in the unicameral Estates of Parliament. When James VI inherited the English throne in 1603, the system was adopted by the Parliament of England. It was also used in the Parliament of Ireland, in the Kingdom of Ireland, from 1613 to 1800, and in the Irish Free State from 1922 to 1936. It is still used in elections to Irish “senate”. For more on this electoral law, see Beloff (1952).

- 7.

These may or may not involve plural voting, in which voters are eligible to vote in or as part of this entity and their home area’s geographical constituency.

- 8.

We refer the readers to Felsenthal and Machover (1998) and Laruelle and Valenciano (2011) for overviews of the theory and its main applications. An alternative measurement approach could be based upon utilities. From the Penrose’s formula (see for instance, Penrose 1946, 1952; Felsenthal and Machover 1998), under IC, utility is an affine function of power. This simple relationship ceases to hold true for other probabilistic models (see, e.g., Laruelle and Valenciano 2011; Le Breton and Van Der Straeten 2015). We have not explored the conclusions in terms of electoral justice drawn from utilities.

- 9.

- 10.

- 11.

In the same vein, see also Durran (2017).

- 12.

Among the differences, note in particular that, as demonstrated by De Mouzon et al. (2020b), the probability of an election inversion (that is an Electoral College winner different from the popular winner) in the Electoral College tends to 0 with the population size for the IAC model while the limit is positive for the IC model.

- 13.

It is sometimes called the IAC* probability model (Le Breton et al. 2016).

- 14.

In addition, the working paper version contains an appendix that does two things. First, we discuss the issue of their asymptotic coincidence in the case of discrete versions of the May and Shapley-Shubik models, and we sketch an explanation of their coincidence/difference in the case of the continuous version. Second, we examine the validity of Penrose’s approximation in the second tier of the Electoral College by comparing the exact ratios of power indices of the states with the ratio of weights.

- 15.

In our simplified setting, like Owen (1975), we neglect the spoiler effects due to the existence of candidates in addition to the two main ones.

- 16.

A general electoral mechanism F is defined as a monotonic mapping from \(\left\{ 0,1\right\} ^{n}\) into \(\left\{ 0,1\right\} \) where \(D\equiv 1\) and \(R\equiv 0.\)

- 17.

Alternatively and equivalently, any electoral mechanism F can be described in terms of winning coalitions. A coalition of voters \(S\subseteq N\) is winning, denoted \(S\in \mathcal {W}\), iff \(F(P)=D\) whenever \(P_{i}=D\) for all \(i\in S\). It is straightforward to check that the family \(\mathcal {W}\) of winning coalitions is monotonic with respect to inclusion. The pair \((N, \mathcal {W})\) is called a simple game (Owen, 2001). Among those, weighted majority games are central. A weighted majority game on N is described by a vector of weights \(w=\left( w^{1},\ldots ,w^{n}\right) \) and a quota q: \(S\subseteq N\) is winning, denoted \(S\in \mathcal {W}(q,w)\), iff \(\sum _{i\in S}w^{i}\ge q\). When \(w=\left( 1,\ldots ,1\right) \) and \(q=\frac{n}{2},\), we obtain the ordinary majority game.

- 18.

In this definition, in both tiers, ties are broken in favor of D. The details of the tie-breaking rule do not impact our results. In fact, our simulations are conducted under the assumption that in both tiers, and ties are broken through a fair random choice between D and R. We will offer further comments on that, later in the paper.

- 19.

The notion of composition is quite general and can be applied to very abstract simple games.

- 20.

This is the “winner takes all” feature of the mechanism. In our paper, we ignore the fact that for Maine and Nebraska“winner takes all” does not fully apply. Strictly speaking, congressional districts should be treated as additional states for the purpose of the modeling. We conjecture that our results are not significantly impacted by this simplification.

- 21.

In the real-world electoral systems which are used to elect the representatives, when the district magnitude is larger than 1, it is often the case that the “winner takes all” principle is replaced by a proportional principle. In such a case, the formal description of the electoral mechanism differs from the one considered here. For a general approach, when the district magnitude is equal to 2, the reader is referred to Le Breton et al. (2017).

- 22.

The House of Representatives has chosen the president only once in 1825 under the Twelfth Amendment. Senate is involved along similar principles in the election of the vice president.

- 23.

\(Piv(i,F,\pi ,n)\) contains a little abuse in notation since \(\pi \) and n cannot be separated as \(\pi \) is defined on \(\left\{ D,R\right\} ^{n}\). \(Piv(i,F,\pi ,n)\) could also be denoted \(Piv(i,\mathcal {W},\pi ,n)\), and it is often called the power of voter i for the voting rule \(F/W \) according to the probability model \(\pi \). When the reference to \(F/W \) will be clear, we will drop it from the notation.

- 24.

This definition needs to be adjusted when the voting mechanism and when ties are not broken deterministically. Let us denote by T (T for ties) the set of profiles \(P\in \left\{ D,R\right\} ^{n}\) such that D is elected with probability \(0<\chi (P)<1\). Assuming that a tie is broken as soon as a single voter changes her mind, then the probability of pivotality is the probability over subprofiles \(P_{-i}\) of having \(F(P_{-i},D)\ne F(P_{-i},R)\). When both outcomes are deterministic, then this happens only when \(F(P_{-i},D)=D\) and \(F(P_{-i},R)=R\). But with ties, this may also happen when : \(F(P_{-i},D)=T\) and \(F(P_{-i},R)=R\) or when \(F(P_{-i},R)=T\) and \(F(P_{-i},D)=D\). In the last two cases, the probability of having different outcomes is not equal to 1 anymore but to \(\chi (P)\).

- 25.

Here, we have only two candidates. The wording IC is used more generally to define the situation of independent and identically draws of preferences over an arbitrary number of candidates. Here, we use the terms Banzhaf and IC equivalently.

- 26.

It can be proved that the Shapley-Shubik model amounts drawing uniformly the number of voters who prefer D to R. It can also be showed that for the IAC model the preferences display some correlation. Here we have only two feasible preferences. For an arbitrary number of candidates, the wording IAC is used more generally to define the situation where the draws of the vectors describing the numbers of preferences of each type are uniform. Here, we use the terms Shapley-Shubik and IAC equivalently.

- 27.

- 28.

If n is odd, then for all i, \(B_{i}=\left( {\begin{array}{c}n-1\\ \frac{n-1}{2}\end{array}}\right) /2^{n-1}\). If n is even, \(B_{i}=\left[ \left( {\begin{array}{c}n-1\\ \frac{n}{2}\end{array}}\right) /2^{n-1}+\left( {\begin{array}{c}n-1\\ \frac{n-2}{2}\end{array}}\right) /2^{n-1}\right] \times \frac{1}{2}\). The assertion follows from Stirling’s formula.

- 29.

This means also that we will not explicitly refer to the division \(n^{1},...,n^{K}\) of the n voters into the K states and to the electoral votes \(w^{1},...,w^{K}\) of the states.

- 30.

Truly only the restrictions of F and \(\pi \) on the subset \(N^{k(i)}\) matter. Since the restriction of F onto \(N^{k(i)}\) is the ordinary majority mechanism with \(n^{k(i)}\) voters, the computation of \(\underline{Piv}(i,\pi ,n)\) amounts to the computation of the pivotality according to \(\pi \) for the ordinary majority mechanism.

- 31.

The exact computation of these values as well as the validity of the Penrose’s approximation is presented and discussed in appendix 3 of the working paper version.

- 32.

When \(K=2\), and \(n^{1}=n^{2}\equiv m\), the probability that any player is pivotal for IAC is equal to \(\frac{(m-1)!}{(\frac{m-1}{2})!(\frac{m-1}{2})!}\times \sum _{r=\frac{m+1}{2}}^{m}\frac{m!}{r!(m-r)!}\times \frac{(\frac{m-1}{2}+r)!(2m-\frac{m-1}{2}-r)!}{(2m+1)!}\), while it equals to \(\frac{1}{m}\times \frac{1}{2}\) for \(IAC^{*}\) and to \(\frac{\left( {\begin{array}{c}m-1\\ \frac{m-1}{2}\end{array}}\right) }{2^{m-1}}\times \frac{1}{2}\) for IC. When \(m=11\), we obtain the values 0.019, \(0.05\) and \(0.123\).

- 33.

There is the place to remind to the reader that \(Sh_{i}\) is also the Shapley value of the TU simple game \((N,V_{\mathcal {W}})\) where \(V_{\mathcal {W}}(S)=1 \) iff \(S\in \mathcal {W}\) and 0 otherwise.

- 34.

This number is often 0. Considering, on the one hand, a State k with an odd number of voters, \(n_k\), there are either no pivotal voters or \(\frac{n_k+1}{2}\) (when there is almost a tie). Considering, on the other hand, a State k with an even number of voters, either there is a tie and half of the voters are pivotal or there is almost a tie and \(\frac{n_k+2}{2}\) voters are pivotal in half of the cases. In all other cases, there are no pivotal voters.

- 35.

Seats of State k are pivotal if \(Seats_{C_k}-Seats_k <= Seats_{-C_k}+Seats_k\), \(-C_k\) denoting the non-chosen party by State k. In presence of a tie (\(Seats_{C_k}=Seats_{-C_k}\) or \(Seats_{C_k}-Seats_k = Seats_{-C_k}+Seats_k\)), only half of the cases are pivotal.

- 36.

The number of electoral votes (called hereafter “seats”) of a state is the sum of its number of representatives and number of senators (which is 2 for all states). The District of Columbia is allocated three seats.

- 37.

To be consistent, we have assumed that District of Columbia has 1 representative.

- 38.

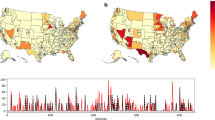

We have also drawn figures with the same y-axis but with the number of electoral votes on the x-axis. These three figures should be compared to the one derived by Gelman et al. (2012) for an econometric model of elections.

- 39.

To achieve this certainty, we have seen that more than a century of computations would be necessary. Another idea, which was not fully implemented here, would be to test the hypothesis with a lower number of voters: for example, dividing state population by 1000. The expected probabilities should be around \(10^{-6}\) instead of \(10^{-9}\), so we could obtain accurate and more precise results with the same number of simulations (\(10^{12}\), and so again in 5 days). Of course, for the sake of comparison, we should do the same with the Banzhaf case. In a former, less efficient version of our simulator, we tested for Shapley-Schubik a population divide factor of 5683, leading to states with population in the interval (100; 6571). But we were able to perform only \(10^{8}\) simulations, at that time, and so ended with the same type of conclusion as here. The obtained probabilities to be pivotal were between \(3.284\times 10^{-5}\) (California) and \(9.680\times 10^{-6}\) (Montana). According to Bienaymé–Tchebychev, those results were significant and accurate (\(\pm 3\times 10^{-6}\)) at a confidence level better than \(95\%\)..

- 40.

We call the attention of the reader on the fact that appendices 1 and 2 in the working paper version shed some light on these questions.

- 41.

To achieve this certainty, we have seen that more than a decade of computations would be necessary. Another idea, which was not fully implemented here, would be to test the hypothesis with a lower number of voters, as suggested in footnote 39.

- 42.

According to Hayes (2012), there are \(0.16976480564070\times 10^{14}\) ways of arriving at a tie roughly 0.75 percent of \(2^{51},\) the total number of profiles in the upper tier.

- 43.

The district of Columbia is not part of the game and in fact in case of a tie, and the rule is to have further votes (as much as needed) as long as a fixed deadline has not expired.

- 44.

So truly, this tie-breaking simple game is itself a compound simple game where the second tier is the ordinary majority game with 50 players \(\left( \left\{ 1,\ldots ,50\right\} ,\mathcal {W}(q,w)\right) \) where \(w=\left( 1,\ldots ,1\right) \) and \(q=25\), and the first tiers are the majority games with the representatives of the states as the basic players.

References

Balinski ML (2005) What is just? Am Math Monthly 112:502–511

Banzhaf JF (1964) Weighted voting doesn’t work: a mathematical analysis. Rutgers L Rev 19(2):317–343

Beloff M (1952) Les sièges universitaires. Rev Fran Sci Po 2:295–302

Chamberlain G, Rothschild M (1981) A note on the probability of casting a decisive vote. J Econ Theory 25:152–162

De Mouzon O, Laurent T, Le Breton M, Lepelley D (2019) Exploring the effects on the Electoral College of national and regional popular vote interstate compact: an electoral engineering perspective. Public Choice 179:51–95

De Mouzon O, Laurent T, Le Breton M (2020a) “One man, one vote” part 2: apportionment, measurement of disproportionality and the Lorenz curve. Mimeo

De Mouzon O, Laurent T, Le Breton M, Lepelley D (2020b) The theoretical Shapley-Shubik probability of an election inversion in a toy symmetric version of the U.S. presidential electoral system. Soc Choice Welfare (Forthcoming)

Droz J (1963) L’origine de la loi des trois classes en Prusse. Rev Histo XIXe siècle 1848 22:1–45

Durran DR (2017) Whose votes count the least in the Electoral College? https://theconversationcom

Felsenthal DS, Machover M (1998) The measurement of voting power: theory and practice, problems and paradoxes. Edward Elgar Publishing

Gelman A, King G, Boscardin WJ (1998) Estimating the probability of events that have never occured: when is your vote decisive? J Am Stat Assoc 93:1–9

Gelman A, Katz JN, Tuerlinckx F (2002b) The mathematics and statistics of voting power. Stat Sci 17:420–435

Gelman A, Katz JN, Bafumi J (2004) Standard voting power indexes do not work: an empirical analysis. Br J Polit Sci 34:657–674

Gelman A, Silver N, Edlin A (2012) What is the probability your vote will make a difference? Econ Inq 50(2):321–326

Gelman A, Katz JN, King G (2002a) Empirically evaluating the Electoral College. In: Crigler AN, Just MR, McCaffery EJ (eds) Rethinking the vote: the politics and prospects of American election reform. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Good IJ, Mayer LS (1975) Estimating the efficacy of a vote. Behav Sci 20:25–33

Hayes B (2012) College ties. Bit player. http://bit-playerorg/publications-by-brian-hayes

Laruelle A, Valenciano F (2011) Voting and collective decision-making: bargaining and power. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Le Breton M, Lepelley D (2014) Une analyse de la loi électorale du 29 juin 1820. Rev Éco 65:469–518

Le Breton M, Van Der Straeten K (2015) Influence versus utility in the evaluation of voting rules: a new look at the Penrose formula. Public Choice 165:103–122

Le Breton M, Lepelley D, Smaoui H (2016) Correlation, partitioning and the probability of casting a decisive vote under the majority rule. J Math Econ 64:11–22

Le Breton M, Lepelley D, Merlin V, Sauger N (2017) Le scrutin binominal paritaire : un regard d’ingénierie électorale. Revue Éco 68:965–1004

Margolis H (1983) The Banzhaf fallacy. Am J Polit Sci 27:321–326

May K (1948) Probability of certain election results. Amer Math Monthly 55:203–209

Miller NR (2009) A priori voting power and the U.S. Electoral College. Homo Oeconomicus 26:341–380

Miller NR (2012) Why the Electoral College is good for political science (and public choice). Public Choice 150:1–25

Mulligan CB, Hunter CG (2003) The empirical frequency of a pivotal vote. Public Choice 116:31–54

Newman EL (1974) The blouse and the frock coat: the alliance of the common people of Paris with the liberal leadership and the middle class during the last years of the Bourbon restoration. J Mod History 46:26–59

Owen G (1975) Evaluation of a presidential election game. Am Polit Sci Rev 69:947–953

Owen G (2001) Game theory, 3rd edn. Academic Press, New York

Penrose LS (1946) The elementary statistics of majority voting. J R Stat Soc 109:53–57

Penrose LS (1952) On the objective study of crowd behaviour. HK Lewis and Co, London

Schilfert G (1963) L’application de la loi des trois classes en Prusse. In: Bibliothèque de la Révolution de 1848, Tome 22, Réaction et suffrage universel en France et en Allemagne (1848–1850)

Shapley LS (1962) Simple games: an outline of the descriptive theory. Behav Sci 7:59–66

Shapley LS, Shubik M (1954) A method for evaluating the distribution of power in a committee system. Am Polit Sci Rev 48:787–792

Shugart MS (2004) The American process of selecting a president: a comparative perspective. Pres Stud Q 34:632–655

Spitzer AB (1983) Restoration political theory and the debate over the law of the double vote. J Mod History 55:54–70

Young HP (1994) Equity in theory and practice. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Acknowledgements

We are very pleased to offer this paper as a contribution to this volume honoring Bill Gehrlein and Dominique Lepelley with whom we had the pleasure to cooperate in the recent years. Both have made important contributions to the evaluation of voting rules and electoral systems through probability models. Power measurement and two-tier electoral systems, the two topics of our paper, are parts of their general research agenda. We hope that they will find our paper respectful of the approach that they have been promoting in their work. Last, but not least, we would like to thank two anonymous referees who have attracted our attention on the imperfections and shortcomings contained in an earlier version and whose comments and suggestions have improved a lot the exposition of the ideas developed in our paper. Of course, they should not be held responsible for any of the remaining insufficiencies. The working paper version, available on the Web sites of the authors, contains three appendices offering supplementary mathematical developments on the intricacies of the Shapley-Shubik’s probability model and its discrete counterpart. The three first authors acknowledge funding from the French National Research Agency (ANR) under the Investments for the Future program (Investissements d’ Avenir, grant ANR-17 EURE-0010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

de Mouzon, O., Laurent, T., Breton, M.L., Moyouwou, I. (2021). “One Man, One Vote” Part 1: Electoral Justice in the U.S. Electoral College: Banzhaf and Shapley/Shubik Versus May. In: Diss, M., Merlin, V. (eds) Evaluating Voting Systems with Probability Models. Studies in Choice and Welfare. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48598-6_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48598-6_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-48597-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-48598-6

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)